[an error occurred while processing this directive]Samuel Lee Palmer and Frances VanWinkle

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

Samuel Lee Palmer, the second of the five Palmer boys and Jane's father, was born in 1841. All his life he had a scar across one cheek, the mark of a burn he suffered as a baby, when, tied into his highchair, he fell into the hot ashes in the fireplace.

The only thing Jane noted as "unusual" in Samuel's life was the time he spent as a sailor on the Great Lakes. Going to Chicago, on his first voyage out of Buffalo, he had to climb up in the rigging to set the sails because he was the only crew member sober enough to go up safely. His other sailing tale was of his experience in the Marine Hospital in Milwaukee, where the sisters were very kind and the Mother Superior was "a merry person and full of laughter." His brief life as a sailor may well explain his absence from the 1880 Federal Census for Michigan.

Although the forest was cleared when the farm on section 16 was broken up and there was no running water on the first 160 acres, Samuel loved it anyway. He was sometimes heard to say to himself a little poem:

Nature the kind old nurse, set the child upon her knee

Said here is a story book, thy Father hath written for thee

And if ever the way grew long and his heart began to fail

She sang a marvelous song, or told a wonderful tale.

Quite naturally, Jane provides more information about Samuel's family than about anyone else. His wife, Frances, was the daughter of the Rev. Peter and Hannah Dunham VanWinkle. Hannah died when Frances was very young, leaving her to act as mother to her younger siblings. She grew up doing church work and played the organ to accompany the singing of the congregation. The family observed their daily worship by reading a chapter in the Bible, starting with the first chapter of Genesis and beginning again when they reached the end. Their father had firm theories about education, one being that geography should not be taught from a text but by maps in every room of the house. Virgil Booth, the oldest son, never liked school and ran away to join the Army at 17 rather than speak a piece at rhetorical exercises. While the rest of the family lived in several different places with their father, Virgil stayed on the family farm where he eventually raised his own family. He arranged to visit his mother, to whom he was devoted, on Sundays, while the family was at church and he could have her to himself. The younger children, however, were reared under their father's influence and were, Jane wrote, "an interesting family." Jane wrote that the descendants of Peter VanWinkle were still living on his farm and that is true today. The lilacs that Hannah Dunham VanWinkle planted over a hundred and fifty years earlier still bloom in the spring.

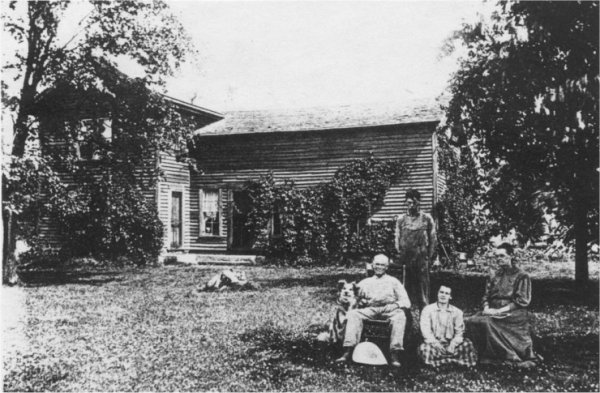

| This is a photo of the old house on section 16. Samuel and Frances are seated in chairs, Jane is on the lawn and William is standing. Frances was "a born student," according to Jane, a woman who liked to solve compound quadratic equations, writing them out in her elegant script. |  |

She said it rested her. Her father recognized her natural bent and wanted to send her, as he had her younger brother, to the university. They quarreled when, in 1874, she married Samuel. (Apparently the couple eloped to Jackson County:

The marriage record shows witnesses with the same surname as the minister's.) They were not reconciled until the birth of her first child. When her father married again, "the family unity was disturbed" once more. Frances read aloud to her children and visited the one-room school they all attended; but she had no love for the country, having spent most of her life until her marriage in towns (or "the city," as Jane put it), as her father occupied one post after another in south central Michigan. The stories her children remembered best hearing her read were those in The Youth's Companion and the tales of Rider Haggard; and they used to hear The Lady of the Lake by Sir Walter Scott as well. Frances loved all books, and it was natural that, when Homer, her eldest son, died at 22 and "the whole pattern of her life changed," she joined a reading club, the Shakespeare Club. The members read every play and then read them all over again. They were shocked by nothing, Jane wrote. Were they not brought up on the Bible?

Samuel prided himself on his efficiency and said, when he husked corn, he could keep an ear in the air all the time. But after dinner, he liked to change his clothes and drive to the village, where a card game was easy to find. He also liked to go fishing with his boys and could dive off the end of the boat into twenty feet of water when he was seventy. He was not a great reader. Ivanhoe was his favorite story and he read it over and over. His old friend and companion in many games of euchre, William Burtless, had Robinson Crusoe as his favorite. Although Frances and her husband were different in their tastes they both "had gentle manners," and were, Jane wrote, "harmonious in their life." Someone told her, "If anyone in your family appreciates your mother, it is your father."

In 1874, shortly after Samuel and Frances were married, William transferred to Samuel the title to the land on which the house stood (the northwest quarter of the northeast quarter of section 16) for the sum of $1500 (though there is some question whether any money actually changed hands). The sale was subject only, according to the Statement of Title, to the "Life Estate of Palmer's wife," i.e., Esther. The quitclaim deed specified that William and Esther had the right to live there till their deaths and that Samuel might not assign the land to anyone else. In 1878, William assigned forty acres of section 16 (the site of the little brown house) to Samuel and forty to Oscar; and in 1883, Oscar sold his share to Samuel. Three years later, only four days before he died, Peter VanWinkle who had bought the forty-acre parcel which Samuel's father had lost to foreclosure, signed a quit claim deed to that quarter to Frances "for the sum of One Dollar and of love and affection between parent and daughter." Samuel signed the deed, and the northeast quarter of section 16 was again completely in the Palmer name.

When he took over the Palmer farm after his father died in 1884, there was very little else but debts. (Jane blamed the family's "many impecunious relatives" and the profligate ways of the Palmers for those debts.) Frances, however, was a frugal Pennsylvania Dutch woman, according to Jane; (The first VanWinkle to come to the United States actually came from Holland [36].) and by the time the youngest of their four children was through high school, all the debts were paid off and the farm was paying its way. In 1914, Samuel bought the sixty-acre tract in section 15 adjoining the Palmer farm to the east from Mary Freeman Bailey, who owned it almost till the end of her life. Then she sold it to Samuel, "everybody seeming to think it ought to be part of the farm."

The two children born in the little brown house were Homer, in 1875, and Jane Kate, five years later, in 1880. Homer died of typhoid fever at Camp Thomas, Chickamauga, TN, where he had gone to train with the Army during the Spanish-American War. The entire community was devastated by his death, the first death in Company C, 31st Michigan. The downtown stores in Manchester closed during the funeral service. An article in the Manchester Enterprise tells the story. Jane was the last person in the family to bear the Palmer name. She never married and she outlived her three siblings, dying in 1972 at age 92. The third child, Ada, always slender and frail (though she was a skillful horsewoman, delighting in driving the team of four on the grain binder), died of tuberculosis when she was twenty, in 1902. Samuel and Frances' youngest son, William Henry, born in 1890, took over the farm at his father's request many years before Samuel died. Samuel gave over its management saying that he might run it in any way he chose that made him a profit. Samuel himself spent most of his afternoons playing euchre with a group of congenial spirits. He was sometimes heard to murmur as he climbed into his carriage on his way to the village, "That boy will never shut a gate." But he was never known to find fault with his son. His usual comment about him was "Let him alone. He's free, white and twenty-one." Jane wrote that father and son shared a taste for luxury tailor-made clothes and the New England conscience, and that both detested advice. Photos make it hard to believe the son was ever very comfortable in anything but overalls.

William, called Bill, was the only one of Samuel's four children to marry; and he married late, at age 47. Laura Worden, who became his wife, was a college-educated city girl and a teacher in a school for the deaf (she herself wore hearing aids); but she apparently settled easily into the life of a farmer's wife. Like Samuel and Frances, the couple seemed able to transcend their differences to live happily together. They had no children. Before their marriage, Bill and Jane, who had shared the family home for some years, had built a new house and had the old one torn down, so Laura moved into that newer house. Jane said a letter was once directed to the family on "The Quiet Road." Laura outlived both Bill, who died in 1969, and Jane. She looked after Jane in her last years and continued to live on the farm on section 16 till her death in 1979. It was she who turned the deeds to the property over to Norman and Virginia Fielder, who lived just down the road from the Palmer house and had been close to Bill and Laura for many years, so close that the Fielder children used to consider the Palmers as a second pair of parents, running to their house when they had disagreements with their own parents. The Fielders bought the Palmer property on section 16--two acres in the mid 1950's, where they built their home, the bulk of it in 1960. They did not take possession till after Laura died, when they inherited the small Palmer estate.

For some years, Jane, who for twenty seven years was the librarian of the Manchester Township Library, where her picture hangs near the Historical Room, lived on the library's second floor. When the library needed more space, she moved to the second floor of Bill and Laura's house, where she stayed till a few years before she died, in 1972, in a nursing home. Who was Jane Palmer? In her day she would probably have been called a spinster. In her writing it is apparent that she was somewhat awed by her mother, and her mother's friends. And, it may be that Jane had reason to feel that she would never measure up. Was she lonely, or was she content, wrapped in the arms of her family's past? We shall never know, for in all that she wrote, she never mentioned herself.

Sources

35. Memoirs of Lenawee County, Michigan

36. A Genealogy of the VanWinkle Family

[an error occurred while processing this directive]